Economy in need: ‘Banking’ on Modi

The Bookkeeper is not insulated from the hysteria surrounding the state of the economy off late. As stated in my last article, the hullabaloo is a modicum of truth enveloped by apocalyptic Whatsapp forwards allegedly initiated by the liberal cabal. What is not helping is the insufficient counter from the Right Wing. When the counter argument does come, it hinges on the basis that the economic slowdown is a transitory impact of demonetization (DM).

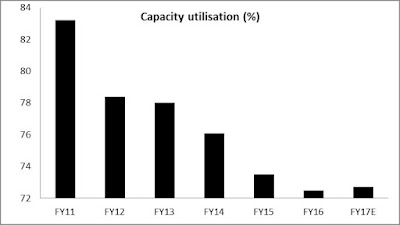

This commentator does not believe it is a transitory effect. This slowdown that has been brewing for a long time is systemic, as indicated by the consistent decline over the past several years in capacity utilization data.

Source:https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2017-04-06%2017:38:57&msec=963&ver=pf

The demand deficit, as falling capacity utilization suggests, is accompanied by a sharp contraction in the returns on capital employed (ROCE). The ROCE for a sample of Indian corporates has fallen to under 3% from nearly 8% in FY11.

Source:https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2017-04-06%2017:38:57&msec=963&ver=pf / https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2017-03-15%2019:40:30&msec=883

The double whammy of falling demand and falling returns has discouraged the private sector from investing in the future. It is no surprise that fresh investments in the corporate sector hit a new low in FY17. As an article in Business Standard puts it: “The average capital spend as a % of revenue was just 5.8% in FY17, growing at the slowest pace since 1992. The combined capex by listed Indian private sector companies grew at a record low of 5 per cent in FY17, against 9.4 per cent, and 5.3 per cent growth in capex reported by listed central public sector enterprises (CPSEs) and Indian subsidiaries of global multinationals (MNCs). This is the slowest growth in capex by the private sector companies in the last 12 years”. As a result, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) contributed only 0.7 percentage points to the real GDP growth of 7.1% (FY17), despite accounting for almost a third of the GDP.

To catalyse the economy, it is rumored that the government may announce a fiscal stimulus in the coming weeks. The Bookkeeper argues that significant financial stimuli have already been given and exhausted. The first was in the form of 7th pay commission and the One Rank One Pension Scheme (OROP). In fact, the Reserve Bank argues that without this outlay, the FY17 GDP growth number would have been lower by 2 percentage points. The second stimulus comes in the form of farm loan waiver schemes announced by different states:

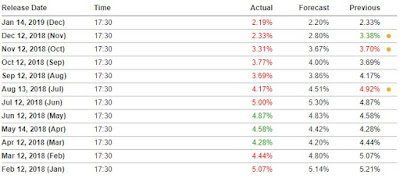

Source: RBI/ various newspaper links

There are reports that if all poll bound states announce farm loan waivers, and extend it to 33% of farm loans in their states, the aggregate amount of farm debt waivers before the 2019 elections would be close to Rs 2 trillion, or a staggering 1.3-1.5% of India’s GDP.

The Bookkeeper believes that while this type of stimuli may provide a temporary bump in GDP, they do not offer a solution to the systemic crises that India stares at. Unless demand is revived and capacity utilization picks up, India is looking at a severe unemployment led crisis further down the road.

The other solution touted is for the Reserve Bank of India to announce deep cuts in the Repo rate. RBI reduced its Repo rate from 8% in December 2014 to 6.25% in June 2017. While this author is all for a lower interest rate regime, practically it does not seem feasible for RBI to make the necessary cuts given the inflation scenario. The RBI tracks not just the headline inflation number, but also the central tendency of inflation data as also its persistence.

Central Tendency: The central typical value of a probability distribution

Persistence: Determines how closely related is a variable at a certain time to its previous value

Source: RBI

The Bookkeeper is no statistician, but he is capable of seeing that the central value (represented by the mean and median) of inflation has crept up over the last three years, enough to worry the RBI.

The only way then to achieve interest rate reduction is to get the banking system to pass through the existing rate reductions to their customers. Despite Repo rates being cut by 175bps (from Dec 2014 to Oct 2017), the spread between the repo rate and the weighted average lending rate (WALR) actually went up by 78 bps. It is only after demonetization that this spread declined, thus finally passing on benefit of RBI cuts after a significant delay.

Source: RBI

The prime reason for the banks anemic attitude is the high level of stressed assets on their books. As at end the of March 2017, RBI estimates that 12.1% advances of the banking system were stressed. Banks, particularly PSU banks, then use the arbitrage between Repo rate and own lending rate to bolster own profitability in an environment where lending is risky and private investment demand is weak. As such, rate cuts do not get passed on. In fact, a regression study quoted by the RBI, indicates that an increase in stressed assets, is associated with higher Net Interest Margins (NIM).

This is where the problem lies. Even though discussion on Banking NPLs has been all but forgotten in the past few months, it is an issue that can no longer be ignored. Banks are the heart of the economy. It is banks that pump the blood of liquidity across various organs of the economic being and unless this issue is tackled, all stimuli, monetary or fiscal will come to naught. It’s about time we acknowledge that the economic slowdown is a real one, with systemic roots, (albeit perhaps exacerbated by a less than optimal rollout of GST) and then tackle this. While the capital adequacy ratio for the system as a whole is 13.3%, various stress test scenarios paint a dire picture for the future. If any bank falls below the statutory minimum CAR, there is likely to be systemic impact and even a possible “run on banks”.

The gargantuan size of bad loans is testimony to the mistakes (or malfeasance?) of the previous government. Stressed assets now estimated at Rs 14 trillion eclipse even the net worth of the entire Indian banking system. The ball is in Narendra Modi’s court now. This isn’t a problem that can be ‘spun’ away, nor one that can be tackled conventionally. It will need creative, out of the box thinking, to come up with innovative solutions. The one thing The Bookkeeper is sure of is, if anyone can it is Narendra Modi. He just has to find the right man for the job.

Very well analysed. The bad loans were a ticking time bomb left by the previous govt which should have been diffused or at least acknowledged publicly as soon as Modi took over.

ReplyDelete