Musings on the Taylor Rule

Summary: While admittedly RBI does not strictly follow the Taylor rule, it is a useful tool in analyzing policy. The current rate stance of RBI implies a trend growth rate of only about 3%, a sharp discount to long term growth target of 7%. RBI would need to cut rates by over 200 bps to reach a level where trend growth of 7% can be accommodated under the Taylor Rule mechanism. While at the current anemic cut size of 25 bps each review cycle, it would take well over a year to reach this level. Analysis of its past rate cuts using the Taylor formula suggests that RBI has been more reactive to output gaps than inflation gaps. This is in itself surprising given how much of the chatter around policy announcements is dominated by inflation data. Given that India is today facing a favourable inflationary gap, as well as negative output gap, it is intriguing to note RBI's continuing gradual approach to monetary policy.

On the backdrop of another anemic cut in rates by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) today, I read an interesting piece on the Taylor Rule by Harsh Madhusudan, and it is recommended reading. It also set me thinking on the Taylor Rule (TR) and its applications and implications for India.

On the backdrop of another anemic cut in rates by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) today, I read an interesting piece on the Taylor Rule by Harsh Madhusudan, and it is recommended reading. It also set me thinking on the Taylor Rule (TR) and its applications and implications for India.

For those who may be unaware, TR is simple mechanism proposed by John Taylor in 1993 that aims to estimate the interest rate should be targeted by the central bank in the country. The formula will make the thrust of the rule evident, and it is brilliant in its simplicity:

Source: LiveMint.com

Very simply, the formula indicates that if inflation is higher than the target inflation, then interest rates in the economy need to be increased. This is so that system liquidity will reduce and prices will soften.

If the GDP growth is higher than the trend growth level, then also the interest rate needs to be increased, thus increasing cost of funds, reducing liquidity causing economic activity to moderate growth, and prevent an overheating of the economy.

Theoretically, if actual interest rate is lower than the level indicated by TR, then the economy has the possibility of over heating. Conversely, if the actual rate is higher than the level indicated by TR, then the it will have a dampening impact on economic growth.

Now instead of calculating the TR rate, I decided to calculate the trend growth implied by the actual rates set by the RBI. So, now the re-arranged formula would look like this:

For the purposes of equilibrium rate I have relied on the rates mentioned by RBI. I believe that the RBI currently considers India's neutral/ equilibrium rate to be 1.25%. This used to be 1.5-2.0% from Jan 2014 to August 2016, and 1.6-1.8% before that. Now since equilibrium rates are given in 'real' terms, I have added the corresponding month's inflation to it to arrive at its nominal avatar.

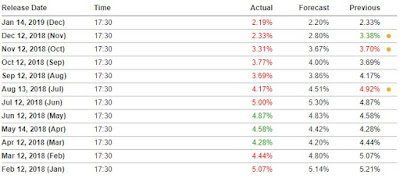

I did this exercise for each of the rate changes over the last ~8 years. The growth trend implied by each new rate is as follows:

The detailed calculations are given in the table below:

Note 1: (errata) The table above has omitted the rate change in June 2015 from 7.5 to 7.25. I do not believe it affects the conclusions or existing calculations.

Note 2: Formal inflation targets were set by the RBI and the government in August 2016. I have assumed the 4% number as the target even earlier given its reasonableness

As can be seen the trend growth was very high, 15-20% between April 2012 to Jan 2014. During this time RBI kept the rate much below that implied by the Taylor Rule (see chart below), assuming that the long term trend of Indian growth is 7%. This may have perhaps contributed to the over heating of the economy given the virtually laissez-faire lending practices followed by banks in this period:

In fact, if the RBI were to solely focus on maintaining the trend growth at 7% basing its policy on the Taylor rule (though some evidence suggests that the TR is not informing the RBI), then RBI would have to keep its policy rate closer to 3%, than the 5.15% it is held at today.

I have given a sensitivity table for what the RBI rate should be at different levels of growth and inflation if inflation target is kept at 4%, and long term GDP trend is held at 7%:

Another interesting observation is that RBI policy rates seem to be driven more by output gaps rather than inflation. This is particularly noteworthy as most of the commentary around policy announcements appears to focus on the inflationary pressures.

What is output gap, and how is it reflected in the TR?

The TR equation itself is made up if three parts. First is the neutral rate, which I have taken as per RBI reports (and is largely constant in its 'real' form). The second part is the inflation situation in the country v. the target levels. The third part is the output gap, i.e. is the actual growth more or less than the trend level (trend is assumed by me to be 7%).

In the chart above, I have decomposed the TR into its inflation and output components. In the period 2013-2015, declines in RBI rates appear to be correlated to the negative output gaps, i.e. periods where GDP growth came out lower than the trend GDP of 7%. Notice how RBI seems to have ignored the significant inflationary gaps (where actual inflation was much higher than the target of 4%). With output gap now significantly negative, and inflation gap also significantly negative, RBI's measured approach may have a detrimental effect on economic activity. I do believe it is time RBI looks at not only its timings of rate reviews, but also the size of cuts.

In conclusion, while admittedly RBI does not strictly follow the Taylor rule, it is a useful tool in analyzing policy. The current rate stance of RBI implies a trend growth rate of only about 3%, a sharp discount to long term growth target of 7%. RBI would need to cut rates by over 200bps to reach a level where trend growth of 7% can be accommodated under the Taylor Rule mechanism. While at the current anemic cut size of 25bps each review cycle, it would take well over a year to reach this level. Analysis of its past rate cuts using the Taylor formula suggests that RBI has been more reactive to output gaps than inflation gaps. This is in itself surprising given how much of the chatter around policy announcements is dominated by inflation data. Given that India is today facing a favourable inflationary gap, as well as negative output gap, it is intriguing to note RBI's continuing gradual approach to monetary policy.

For the purposes of equilibrium rate I have relied on the rates mentioned by RBI. I believe that the RBI currently considers India's neutral/ equilibrium rate to be 1.25%. This used to be 1.5-2.0% from Jan 2014 to August 2016, and 1.6-1.8% before that. Now since equilibrium rates are given in 'real' terms, I have added the corresponding month's inflation to it to arrive at its nominal avatar.

I did this exercise for each of the rate changes over the last ~8 years. The growth trend implied by each new rate is as follows:

The detailed calculations are given in the table below:

Note 2: Formal inflation targets were set by the RBI and the government in August 2016. I have assumed the 4% number as the target even earlier given its reasonableness

As can be seen the trend growth was very high, 15-20% between April 2012 to Jan 2014. During this time RBI kept the rate much below that implied by the Taylor Rule (see chart below), assuming that the long term trend of Indian growth is 7%. This may have perhaps contributed to the over heating of the economy given the virtually laissez-faire lending practices followed by banks in this period:

In fact, if the RBI were to solely focus on maintaining the trend growth at 7% basing its policy on the Taylor rule (though some evidence suggests that the TR is not informing the RBI), then RBI would have to keep its policy rate closer to 3%, than the 5.15% it is held at today.

I have given a sensitivity table for what the RBI rate should be at different levels of growth and inflation if inflation target is kept at 4%, and long term GDP trend is held at 7%:

Another interesting observation is that RBI policy rates seem to be driven more by output gaps rather than inflation. This is particularly noteworthy as most of the commentary around policy announcements appears to focus on the inflationary pressures.

What is output gap, and how is it reflected in the TR?

The TR equation itself is made up if three parts. First is the neutral rate, which I have taken as per RBI reports (and is largely constant in its 'real' form). The second part is the inflation situation in the country v. the target levels. The third part is the output gap, i.e. is the actual growth more or less than the trend level (trend is assumed by me to be 7%).

In the chart above, I have decomposed the TR into its inflation and output components. In the period 2013-2015, declines in RBI rates appear to be correlated to the negative output gaps, i.e. periods where GDP growth came out lower than the trend GDP of 7%. Notice how RBI seems to have ignored the significant inflationary gaps (where actual inflation was much higher than the target of 4%). With output gap now significantly negative, and inflation gap also significantly negative, RBI's measured approach may have a detrimental effect on economic activity. I do believe it is time RBI looks at not only its timings of rate reviews, but also the size of cuts.

In conclusion, while admittedly RBI does not strictly follow the Taylor rule, it is a useful tool in analyzing policy. The current rate stance of RBI implies a trend growth rate of only about 3%, a sharp discount to long term growth target of 7%. RBI would need to cut rates by over 200bps to reach a level where trend growth of 7% can be accommodated under the Taylor Rule mechanism. While at the current anemic cut size of 25bps each review cycle, it would take well over a year to reach this level. Analysis of its past rate cuts using the Taylor formula suggests that RBI has been more reactive to output gaps than inflation gaps. This is in itself surprising given how much of the chatter around policy announcements is dominated by inflation data. Given that India is today facing a favourable inflationary gap, as well as negative output gap, it is intriguing to note RBI's continuing gradual approach to monetary policy.

Comments

Post a Comment