Admittedly, this is a very late addition to my blog. Perhaps it is not contemporary but in some ways I think this is the best time to analyze the farm bills away from the politically charged atmosphere of a few years ago. Notably, this isn't the first time the Modi government has taken a step back, the first time I recall being the land bill. Till the country decides to undergo a mindset change, freebie and vested interest culture cannot be done away with laws. People should want a better life.

A caveat before I begin: I am not a lawyer or a farmer, and my understanding of the situation comes from reading both mainstream and social media. In case something is factually incorrect, please point out in comments with supporting links to official pages. Rest all is politicking.

In a light hearted vein I will begin the post by asking: How have villains in Hindi films changed over the years? Well, broadly speaking:

Black and white era – Zamindar

Technicolor era – Black marketer

Modern films – Politicians

In every era, the villain is someone who exploits the people. And what is the source of this exploitation? Food.

So why was the Zamindar evil? Because he hoarded produce from his farmlands.

Why was the black marketer evil? Because he hoarded food in his godowns.

Why is the politician evil? Because he controls everything.

Now coming to how Indian agriculture was structured in light of the above:

The Essential Commodities Act (ECA) was first passed in 1955 to stop the hoarding of essential commodities, farm produce for the sake of this document. So it basically tackled the evil Zamindar who could no longer starve the nation till the prices reached astronomical levels. The 2020 farm laws contained a update to this Act, as the world has changed in the last half a century.

Now because the farmers were forced to sell (i.e. couldn't hoard their produce) more or less immediately after a harvest, it invariably created a new choke point. It shifted the power of price to the buyer. The buyers (agents/ wholesalers etc.) unofficially formed a cartel and would only buy farm produce at very low prices. So the government did two things:

1) It formed the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) - established by the state government (1960s-1970s)

2) The Central government decided to publish Minimum Support Price (MSP) - on 23 crops (1965)

I don't know whether it was regulatory capture by black marketers, or corruption at a political/ bureaucratic level, or sheer incompetence, but this is where it gets tricky:

Only those agents who had a APMC license could buy farm produce, and farmers could sell their produce only to such agents. The MSP also was not a mandatory level, but merely a guideline (a point we will come to later). So basically these moves made a bad situation worse and further skewed away from a free market. What happened was the unofficial cartel turned into an official cartel! Now APMC buyers could force farmers to sell goods dirt cheap knowing that the ECA forced them to sell immediately, and the APMC forced them to sell to license holding buyers only. So even if a third party was willing to pay 100 times the price, the farmer was FORCED to sell to the APMC agent, by law. The MSP did not help either, as only 6% of farmers got it - since it was not mandatory (from the

Shanta Kumar Committee report).

Coming to the farm bill now. The Bill contained three parts, and we shall see how they tackled the above situation:

1) The Essential Commodities Bill 2020: This changed the provision that stopped farmers from storing their produce. This law now allowed farmers to hoard as much produce as they wanted in their own warehouses and only when they felt that the price was right, they could bring it to the market. This returned the pricing power back to the farmer.

2) Farmers trade and commerce act 2020: This allowed farmers to sell to anyone instead of the current situation where they are being forced to sell only to APMC licensed agent from the local mandi.

3) Farmers agreement on price assurance and farm services 2020: This law allowed farmers to agree to sell their produce at pre-fixed price much before the crop is even harvested. The law allowed for creating even a crop insurance if the crops are destroyed in a famine or locust attacks etc. This law allowed companies like Starbucks, Cargill, Jio, Tata etc. to sign such forward contracts with farmers

It is apparent that these three bills for the first time were taking India's agriculture market towards a free market economy instead of away from it. The government would still continue to publish MSPs as it has for decades and there would be no change in that arrangement.

These laws put power back into market forces: i.e. a farmer would produce that crop which he thought would give him the best price. The best price would be determined by demand and supply (as it happens everywhere else in the sane world), and then the farmer could pick who he wants to sell to. To protect against price fluctuations he could enter into forward selling agreements with large buyers, and even take out insurance against crop destruction. Basically, these laws would have ushered Indian agriculture into the modern age.

So why are farmers protesting? Well most of them aren't. Because the biggest demand from the so-called farmer's union is for the government to make the MSP mandatory. The current MSP guidelines have been in place for over 50 years, so the first question is, "why was this demand not being made earlier?" The second question is "If only 6% of farmers benefit from MSP, then would making it mandatory not make it elitist?" In essence farm bills were being opposed for something that isn't changing, and impacts only 6% of the farmers anyway. Absurd, isn't it?

But lets say, this is a political argument (despite it being a fair one), i.e. why are you complaining now when you haven't complained for half a century.

Lets look at it rationally as well. If it is of no consequence, why wouldn't Modi just agree to the demand and make it mandatory for people to purchase agricultural produce at fixed prices, that keep rising every year.

Here is the natural reason now: Lets say, I can use my land to produce crop A, or I can produce crop B. Normally, I would produce crop A for a certain part of the year, and crop B during another part of the year. In a compulsory MSP regime, prices will be fixed at some Rupees per quintal. It stands to reason that different crops will have differing yields. For example, rice paddy which is heavily water consuming, has a yield of 24 quintals per hectare of farm. An alternative crop like red gram, has a 4 quintal per hectare.

Now if govt guarantees a price for paddy, then why will the farmer plant red gram at all? He will plant rice through the year, not allowing the natural cycle of soil replenishment to take place. The soil degrades, and water is wasted because nature did not intend for the same patch of land to be exploited in the same way for decades on end. Inevitably, chemicals need to be added to keep pushing out rice from a land that wasn't meant for it. And I am not even speaking philosophically, look at the croping pattern data below:

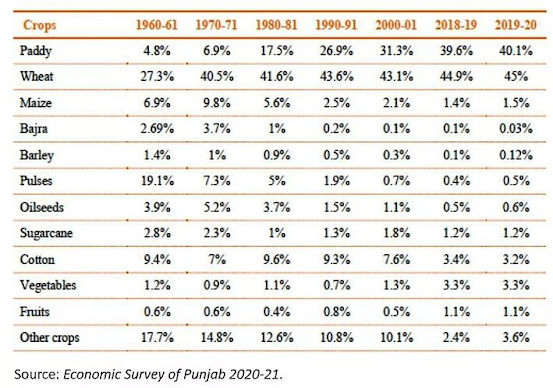

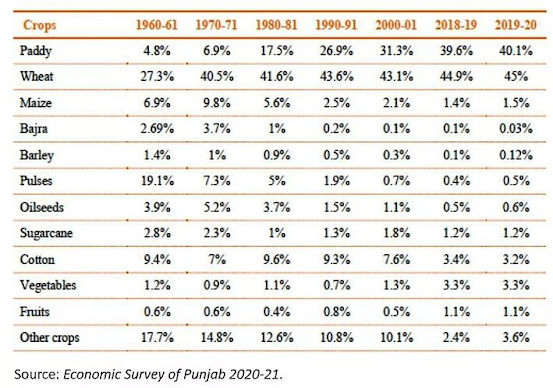

Share of rice cultivation in Punjab, which isn't even a rice consuming state, has gone from 4.8% to 40.1%. Pulses has dropped from 19.1% to 0.5%. We see similar changes in Maize, Bajra, Barley, Oilseeds etc. Imagine the state known for "makke di roti and Sarson ka saag" is hardly producing maize and pulses any more! This is madness! Imagine the hardship the soil in that state faces to produce things that are largely non-native (at least in scale) to the region. This may result in depletion of water tables, and long term (perhaps permanent) degradation of soil. It is three generations later that the farmers there will see the irreparable damage that is being caused now.

Now lets also look at the economic reason: As we have seen above, farmers will keep churning out supply of their most profitable crop. Its a simple equation, that which is more in supply will see its price drop. So we will be guaranteeing a higher and higher price for a crop that is more and more in supply. We have all seen news/ photos of wheat and rice crops rotting away in government godowns. This is basically the surplus that has been produced due to the skewed economics of price guarantees devoid of connection to reality. And who bears the burden? The tax payer. Because it is our money that is being spent to make these purchases. The private sector will not stand for this circus. I recall an example in Maharashtra were traders were forced to buy

Tur Dal at MSP, otherwise be put in prison. Because the economics made no sense to traders, they agreed to go to jail instead of buying something at a price higher than what they can sell it. Its basic economics.

Finally, lets look at a practical reason: And that is, MSPs are irrelevant in a new farm law regime. if farmers are allowed to bring produce to the market only when they think they can get a fair price, if they are allowed to have forward contracts with price guarantees, if they are allowed to sell to whomsoever they want, and they are able to guard against natural calamities via insurance, why would they need MSP at all? E.g.: If you produce wheat, and think that the price needs to rise 15% for you to get a fair return on your investment, simply store it till the price rises. Or better yet, fix the prices of the produce even before planting a single seed. Dont plant if you dont think the forward price is fair, and plant the higher yielding crop instead. Where does the need for MSP enter into this at all?

In hindsight, the easiest thing for Modi would have been to agree to make the MSP mandatory and get the laws passed. but it is my opinion that keeping the natural, economic, and practical reasons in mind he did the harder thing (politically) of retreating than allowing long term damaging things to become laws.

In this he was defeated by the villain of the modern Hindi films: The opposition politician.

Comments

Post a Comment